“I shall plant my hands in the garden

And I will grow. I know. I know.”

“Look at Forough’s birth certificate,” Professor Milani directed, pointing to the screen on the wall of the lecture hall.

Farzaneh Milani, an Iranian-American scholar of Middle Eastern Studies, was invited to SOAS University of London to inaugurate a series on Persian literature this week. They couldn’t have picked anyone better – she unapologetically extols Forough Farrokhzad, a prolific poet who came to a tragic end at the tender age of 32.

“You can see the date of her birth, her parents’ name,” Professor Milani continued while about forty heads, mostly Iranians, craned their necks to get a better look at the digital copy of the old, faded document.

“But the death page is blank – no stamp, no date.”

Her voice, though soft and measured, resonated with an unmistakable glint of excitement through the lecture hall. “Forough is still running.”

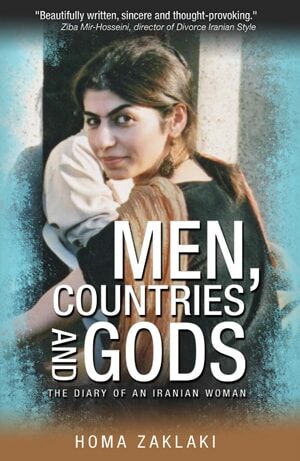

What is it about Forough Farrokhzad that has made her an Iranian icon? How come, fifty decades after her death, women from all walks of life – respectable scholars and heart-broken teenagers alike – are all so enchanted by her? Why did we choose Forough of all Iranian artists as our protagonist’s lighthouse in “Men, Countries and Gods”? Why does she resonate with us, this sorrowful poet who shamelessly wrote: “I sinned, a sin all filled with pleasure, next to a shaking, stupefied form. O God, who knows what I did, in that dim and quiet place of seclusion.”

Thinking back, Forough’s name first popped up in my childhood along with words like divorce and lovers – both taboo in Iran. For some, her name was synonymous with “filthy” and “tramp”.

It was only in my late teens – in fact, it was during my very last visit to Iran – that an old school friend, pining for her sweetheart, pressed a collection of Forough’s poems into my hands as a farewell gift.

From then on, Forough kept me company in Vienna, during my lunch-breaks in high school, on tram rides, in cafes; I wrote her impassioned words for friends on their birthday and wedding cards. Her poems moved with me to the UK, and I carried them from one hospital accommodation to the other before finally settling in London. Like nearly every other girl, I too read them at the exciting beginning, in the confusing middle and at the suicidal end of each love.

Forough’s pull for me has always been her courageous femininity, the intimacy in her poems, the way she pours herself into her writings. It takes courage to turn to flesh, the corporal and the sensual when most seek to distance themselves from earthly matters. She descends head on into the muck when all others seek to ascend. Don’t get me wrong, I love Hafez and Rumi too. I love the depth and the wisdom of their intoxicating love poems, but Forough is somehow realer in her writings. Hafez and Rumi seem to be in control; Forugh disappears and yet always resurrects.

It is said that once an interviewer told Forough, “People say you write like a woman.”

She responded, “You know I am glad I do. Because I am a woman.”

Professor Milani says that she’s often asked to officiate her students’ weddings, and regardless of their nationality, they all choose Forough’s poems because, in her words, “no one else has written such beautiful love poems” than this woman. Forough shouts out “I love you” in a culture where, as Milani observes, custom requires that a bride play coy at her wedding ceremony and respond with silence when asked for her consent to the marriage, only after being posed the same question three times is she allowed to provide her consent by whispering yes.

Forough, instead, shouts: “Yes, yes, it is the beginning of love and although the end is uncertain, I am not afraid of the end as love is enough.”