“If you believe you are a citizen of the world, you are a citizen of nowhere.” By now most of you must have heard these crass words from the British Prime Minister, Theresa May. Many were taken aback or felt downright offended by her view, but if we are honest, we know that she struck a chord with far too many people.

Theresa May was clearly playing on our tribal instincts and xenophobic defences, on that part of us that longs for sameness and like-mindedness as a synthetic source of certainty, safety and connection. These are, after all, real and justified human needs. When we are surrounded by people we know – i.e. people who are like us – there is a false feeling of security, an unjustified complacency that results in an absence of constantly being alert and watching our backs. Whether or not it’s an accurate perception, we like the secure feeling it brings us, don’t we? We like orderly packed things, fixed concepts, preferably black and white.

Even though we often make claims to the contrary, when it really comes down to our daily choices, we’d rather have a world that resembles our public bathrooms: men and women, clear and distinct categories – binaries are such friendly tools. A third category only complicates things and instigates a sense of confusion and threat. We can work with Venus and Mars, but it’s easier if the rest of the solar system remains little more than a theoretical concept that we can easily keep at arm’s length. Anything more than that is scary.

“Where are you from?” is an understandable question of interest and compatibility, especially in this time of mass migration. By obtaining a one-word answer, we will know where we’re standing, who we are dealing with, how to treat them and even perhaps how much to trust them.

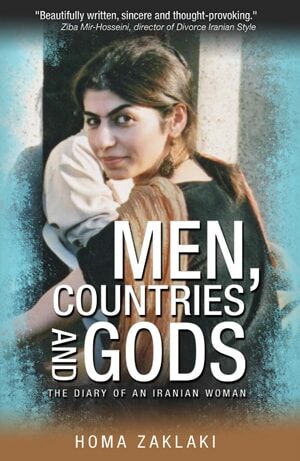

God forbid, when someone like me can’t provide a clear cut answer. I am not truly an Iranian, I am definitely not an Austrian and in no way am I British. You see, there’s no effortless location I can come up with to help identify my tribe.

“Where is home for you?” is another question I dread. When the British voted to leave the EU, and I expressed a feeling of being rejected and devalued as a human being, my non-British friends thought I was overreacting. But I knew with everything inside of me that I wasn’t. When you don’t have a home to go back to, you feel damn forlorn when they tell you to go home.

Aside from the security checkpoints, the only place I truly feel at home is in an airport and on the subsequent flight, forty thousand feet in the air, floating between countries and continents, those no man’s lands, borderless in-betweens.

Having been a foreigner all my life, I can’t sincerely embrace the citizenship of one nation. Being a world citizen is the only authentic option left for me. The world – and expressly not the narrow confines of specific nations – is what provides me with the only firm ground from which I can relate and respond to others.

When we try hard to safeguard a clear sense of identity and belonging, we deprive our lives of expansion, growth and meaning. These are inherent to human nature – and not at odds with certainty, safety and connection. It serves all of us best when we don’t let anyone play our need for safety against our needs for connection and inclusiveness. If we shift our narrow gaze just slightly, we will inevitably recognise the world as our home. In fact, as world citizens, we can hold the entire world in our hearts and stay responsible and loyal, not to nowhere, but to NOW and HERE. Wherever we find ourselves, we are home because the world is our home.